相比其他脊髓损伤,创伤性颈脊髓损伤(trauma cervical spinal cord injury, TCSCI)是最严重的创伤,更易造成不可逆的身体和心理障碍。据估计创伤性脊髓损伤(trauma spinal cord injury, TSCI)发病率为23/100 0000,该疾病可导致医疗服务的成本上升[1]。在TSCI中,颈椎损伤约占40%~60%。研究表明,约有每月收入的19%用于支付该疾病的治疗,会加大家庭的经济负担,同时会影响社会经济发展[2]。由于颈脊髓损伤缺乏有效治疗方法,因此,干预颈脊髓损伤的发生对社会经济的稳定发展有重要作用。

许多国家,特别是在发达国家报道了创伤性颈脊髓损伤流行病学的特点[3-6]。然而,大多数亚洲国家并没有从国家层面进行创伤性颈脊髓损伤流行病学研究[7]。据统计,2012年,中国有超过100 0000例的脊髓损伤患者,每年会增加10 000至60 000例新患者。在中国,仅有少数城市或省份分析了其流行病学特点[8-11],但是广西地区仍然缺乏调查资料。作为中国西南地区最大的一家医院,广西医科大学附属第一医院接收大量创伤患者的治疗和康复。本研究通过收集和分析从2012年1月1日至2017年12月31日在广西医科大学附属第一医院就诊的创伤性颈脊髓损伤患者的流行病学特征,为疾病预防策略实施和有效分配医疗资源提供依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料本研究为回顾性调查研究,收集自2012年1月1日至2017年12月31日在广西医科大学第一附属医院收治的外伤性颈椎骨折合并颈脊髓损伤患者。通过检索患者病案号,查阅原始病历获得包括年龄、性别、婚姻状况、发病时间、住院时间、创伤机制、颈脊髓损伤节段、ASIA分级、合并症、并发症及是否死亡在内的详细数据。疾病诊断符合ICD-10诊断编码。从本研究原始数据库中提取的数据包括:年龄、性别、职业、入院日期、住院时间、创伤机制(从高≥2米或从小于2 m的坠落;汽车事故;摩托车事故(MVA);物体击打等)、颈脊髓损伤节段、ASIA分级、合并伤、并发症和是否死亡。患者按年龄段划分不同组:< 15岁,15~24岁,25~34岁,35~44岁,45~54岁,55~64岁,65~74岁和≥75岁。根据ASIA脊髓损伤的神经功能分类国际标准来评估损伤神经水平和脊髓损伤的程度。

1.2 纳入和排除标准将在广西医科大学附属第一医院住院治疗的创伤性颈脊髓损伤患者纳入研究,同时排除以下病例:(1)非急性创伤颈脊髓损伤患者;(2)重型颅脑损伤患者;(3)ASIA E级患者;(4)缺乏MRI检查的患者。

1.3 统计学方法统计分析采用Microsoft Excel收集整理。

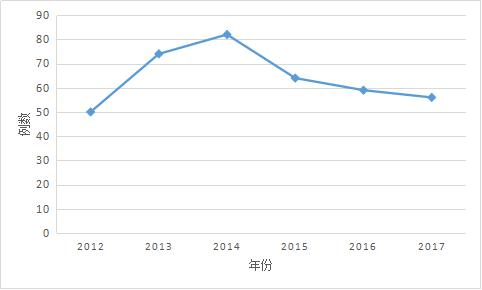

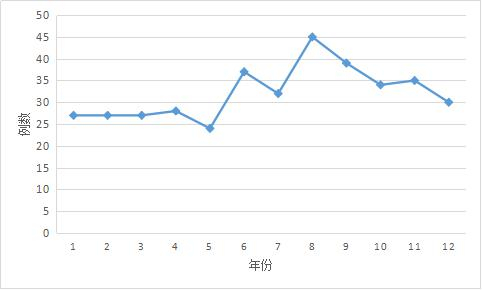

2 结果 2.1 人口分布特征如表 1所示,385例患者中314例为男性,女性71例,男女比例为4.4:1,年龄(47.9±13.8)岁,男性(48.3±13)岁,女性(46±13)岁,年龄范围2~82岁,人数最多的年龄组为45~54岁,占31.6%,其次是35~44岁(20.2%)和55~64岁(21%)。职业分布特点如下:农民,工人,失业、退休、职工和其他职业分别为61.8%,15%,4.9%,5.4%,7%和6%,创伤颈脊髓损伤发生率有上升趋势,于2014年达到高峰,之后逐年下降,每年的八月是高峰期(图 1~2)。

| 指标 | 2012年 | 2013年 | 2014年 | 2015年 | 2016年 | 2017年 | 合计 |

| 性别 | |||||||

| 男 | 43 | 62 | 67 | 53 | 47 | 42 | 314 |

| 女 | 7 | 12 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 71 |

| 婚姻状态 | |||||||

| 已婚 | 45 | 63 | 76 | 57 | 51 | 50 | 342 |

| 未婚 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 43 |

| 职业 | |||||||

| 农民 | 27 | 48 | 49 | 44 | 37 | 33 | 238 |

| 工人 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 8 | 17 | 2 | 57 |

| 职员 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 27 |

| 退休 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 21 |

| 无业 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 19 |

| 其他 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 23 |

| 年龄(岁) | |||||||

| < 15 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 15~24 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 22 |

| 25~34 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 39 |

| 35~44 | 9 | 17 | 15 | 13 | 9 | 15 | 78 |

| 45~54 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 23 | 18 | 17 | 122 |

| 55~64 | 11 | 17 | 15 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 81 |

| 65~74 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 32 |

| ≥75 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| 病因 | |||||||

| 地处坠落 | 9 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 15 | 27 | 113 |

| 高处坠落 | 22 | 19 | 27 | 16 | 20 | 28 | 132 |

| 轿车事故 | 5 | 17 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 20 | 78 |

| 摩托车事故 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 41 |

| 物体击打 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 27 |

| 其他 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 27 |

| ASIA分级 | |||||||

| A级 | 14 | 26 | 28 | 19 | 26 | 21 | 134 |

| B级 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 33 |

| C级 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 29 | 19 | 24 | 137 |

| D级 | 13 | 13 | 22 | 13 | 12 | 8 | 81 |

| 合并伤 | |||||||

| 脑外伤 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 20 | 15 | 93 |

| 胸部损伤 | 8 | 15 | 14 | 7 | 12 | 8 | 64 |

| 腹部损伤 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| 四肢和骨盆 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 22 |

| 无 | 35 | 43 | 62 | 48 | 34 | 26 | 248 |

| 并发症 | |||||||

| 呼吸道感染 | 17 | 29 | 32 | 26 | 24 | 27 | 155 |

| 泌尿系统感染 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 52 |

| 深静脉血栓 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 20 |

| 压疮 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 27 |

| 高钠血症 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 18 |

| 高钾血症 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 12 |

|

| 图 1 创伤性颈髓损伤每年的发病例数 Figure 1 The annual incidence of TCSCI |

|

|

|

| 图 2 创伤性颈脊髓损伤每月的发病情况 Figure 2 Incidence of TCSCI per month |

|

|

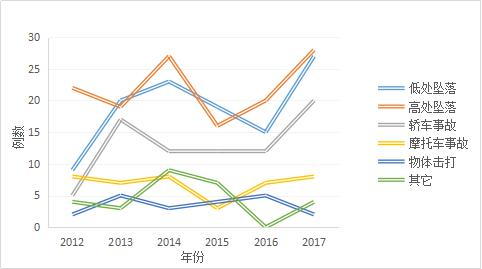

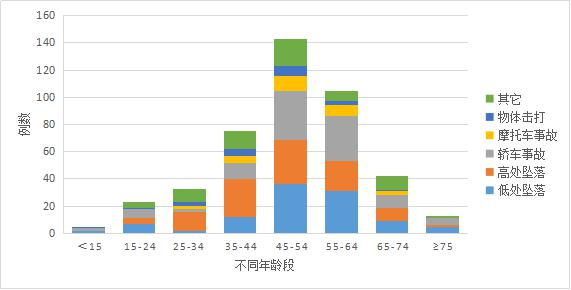

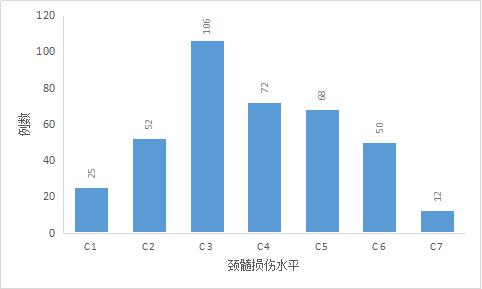

颈脊髓损伤的最常见的原因是坠落(63.5%)(包括从高处和低处),其次是交通事故(20.2%)。大多数坠落的高度≥2 m(34.2%),低处坠落伤最常见年龄45岁(65.7%)。创伤相关的损伤是最常见的35~64岁组(图 3)。209例患者无合并损伤,合并颅脑损伤83例(47.1%),其次是胸部损伤54例(30.6%),多部位损伤62例(图 4)。在所有385例患者中,最常见的颈脊髓损伤水平是C3(106例,27.5%),其次是C4水平(72例,18.7%)和C5(68例,17.6%)(图 5)。在损伤分级中,A级为34.8%,B级为8.5%,C级为35.5%,D级为21%(表 1)。

|

| 图 3 坠落导致损伤的每年发病例数 Figure 3 The trend of falling in the studied period |

|

|

|

| 图 4 不同年龄组创伤机制的分布 Figure 4 The distribution of trauma mechanism in different age groups |

|

|

|

| 图 5 创伤性颈脊髓损伤患者的损伤水平分布 Figure 5 The injury level of TCSCI |

|

|

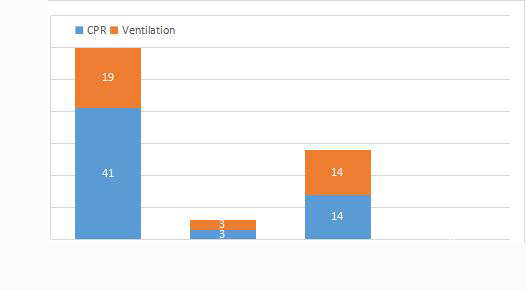

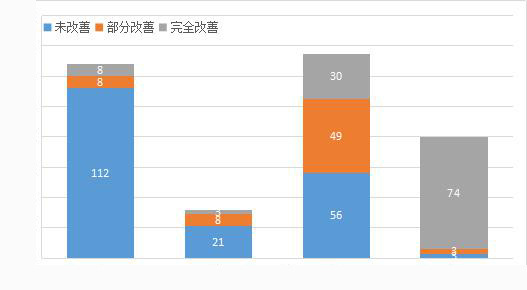

住院期间,58例患者接受了CPR,36例患者需要机械通气(图 6),284例患者存在并发症,154例(54.5%)发生呼吸道感染,其次是尿路感染52例(18.3%),深静脉血栓(DVT)20例(7%)和褥疮27例(9.5%),见表 1。所有患者住院时间为(26.5±21.6)d。与没有合并损伤的患者比较,颈脊髓损伤合并其他损伤时患者的住院时间为(26.3±19.8)d。院内并发症患者的住院时间(33.3±24.3)d,明显长于没有并发症患者的住院时间(21.7±16.3)d。ASIA A级患者的住院时间更长(30.2±28.4)d,明显长于其他分级患者[B级(25.4±14.4)d,C级(27.0± 15.8)d,D级(21.2±18.2)d]。死亡10例,其中9例男性,1例女性。1例死于多器官功能衰竭,7例死于呼吸系统疾病,2例死于心脏衰竭。出院时,192例患者肌力未改善,68例患者部分改善,115例患者完全改善,见图 7。

|

| 图 6 损伤分级与心肺复苏、机械通气关系 Figure 6 Relationship between ASIA grade and CPR and auxiliary ventilation |

|

|

|

| 图 7 损伤分级与肌力改善情况 Figure 7 Improvement of muscle strength in patients with ASIA classification |

|

|

本研究纳入广西医科大学第一附属医院2012年至2017年6年间385例TCSCI患者,分析其流行病学特点。纳入研究的TCSCI患者中男女比例4.4:1,与目前的一些文献报道类似[7-8]。男性是从事高风险职业人群,相对而言女性主要从事家务或者风险性更小的工作。从职业分布上看农民最多,其次是工人。与国内外一些学者报道的以无业者为主的职业分布不一致[10, 12-13]。患者的职业分布的差异可以解释为:(1)广西是中国西南部的一个欠发达地区,农民占人口的大多数;(2)随着经济的发展和中国社会的现代化,越来越多的农民在城市从事城市建设。

在国内,35~60岁人群是社会的主要劳动力。在本研究中,35~64岁的患者占72.9%,受伤年龄在2~82岁,年龄为(47.9±1.38)岁,这与国内某些省份流行病学调查一致[4, 6-7]。在交通事故造成的患者中,91%患者的年龄小于60岁,与老年人相比,年轻人和中年人更容易在交通事故中受伤。本研究与某些研究者报道一致,< 50岁患者更容易出现创伤性颈脊髓损伤[8, 14-16]。但是,随着中国社会的老龄化发展,今后会有更多的老年人参与社会工作并面临受伤的危险。

目前缺乏创伤性颈脊髓损伤的发生与具体好发时间的关系。国内有学者认为,冬季滑雪是创伤性颈脊髓损伤的主要原因[8]。另外有国外学者报道,每年的5月和8月份是高发月份,但是没有分析具体原因[17]。本研究发现,2014年损伤患者数量到达高峰值,随后下降。5月至8月呈现上升趋势,随后下降,暂时无法解释这种现象,但笔者认为政府部门在这几个月份,应该加大宣传力度,提高自我防范,增加相应医疗服务。自2015以来,广西各医院建立了双向转诊和三级医院诊疗制度,这或许能解释2015年之后本院此类患者下降的趋势。

在一些发达国家最常见的颈脊髓损伤的原因是高处坠落[18-20],而在一些欠发达国家,车祸是导致颈脊髓损伤的主要原因[16],尤其是没有佩戴安全帽的摩托车驾驶员,颈脊髓损伤的概率更高[21]。毫无疑问,区域差异可能导致不同的损害机制。在过去的10~20年间,跌倒或坠落是天津市颈脊髓损伤的主要原因;而北京则是由于车祸导致这类损伤的发生[19]。本研究发现,从2012至2017年间,坠落或跌倒成为广西地区TCSCI的主要原因,其次是车祸。分析以下几个原因可能导致本研究与国内其他地区损伤机制差异:(1)随着国内相关法律的完善,酒后驾车、超速、不规范的驾驶行为都有明显的抑制作用。交通事故造成的损伤不是主要原因。(2)广西是一个多山的地区,农民从事这些区域的日常工作。(3)随着社会经济的快速发展,越来越多的城市高楼众多,导致高处坠落的风险增加。(4)攀岩已经成为广西省的年轻人中流行的运动。

最常见的颈脊髓损伤部位是C3水平(106例;27.5%)其次是C4水平(72例;18.7%)和C5水平(68例;17.6%),本研究结果与陈坤等[22]的研究结果类似。本研究中C3损伤最常见的原因是低处坠落(33.7%),其次是交通事故(28.3%)。TCSCI是非常严重的脊髓损伤,往往合并有其他部位的损伤,包括胸部、腹部、头部和面部等。本研究发现,脑外伤是最常见的合并伤,其次是胸部创伤。TCSCI合并创伤性脑损伤的发生率为16%~60%[18]。TCSCI合并其他损伤,尤其是胸部损伤和脑损伤,通常增加治疗难度和延长住院时间。因此,在TCSCI早期,应重视合并伤的诊断和治疗,降低病死率。了解并发症的发生,对制定TCSCI预防策略非常重要。本研究发现TCSCI患者常常发生以下并发症:肺部感染(54.5%)、尿路感染(18.3%)、DVT(7%)和褥疮(9.5%)。本研究缺乏长期随访数据导致长期并发症资料缺失。据其他研究的长期观察表明,性功能障碍和肠/膀胱功能减退、抑郁和慢性疼痛、皮肤脱落是最常见的长期并发症[18, 23]。本研究的患者的住院时间为27.9 d,明显低于一些报道中的住院时间。可能与康复专业人员的短缺有关,只有一小部分人可以在脊髓损伤后立即接受常规康复治疗,且康复成本大、时间长,一些患者无法继续支付治疗费用。

全球范围内TCSCI的病死率在1.3%~22.2%。这项研究发现,ASIA A级患者辅助通气(52.7%)和心肺复苏(70.8%)风险高于其他分级患者。此外损伤越严重,患者的预后越差。87%的ASIA A级患者未恢复肌力,且出院后,患者生活不能自理。在中国,疾病导致的死亡登记往往是在住院期间,因此在我国该类患者的病死率更低。结合本研究低病死率,分析原因:(1)病死率的报告只包括那些住院患者;(2)根据中国传统习俗,患者最后自动出院回家和家人一起度过最后的时间;(3)随着医疗条件的改善,病死率会逐步下降;(4)中国医疗保险的覆盖率还不高,没有足够的资源来支付与抢救危重患者的相关医疗费用,所以这些患者选择放弃治疗而自动离院。

本研究的局限性:首先,为单中心研究结果,;其次,损伤机制和病因缺失;第三,为回顾性分析,研究的准确性需要通过前瞻性而改进。但对了解本地区的TCSCI流行病学特点仍有借鉴作用。

| [1] | Chiu WT, Lin HC, Lam C, et al. Review paper: epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury: comparisons between developed and developing countries[J]. Asia Pac J Public Health, 2010, 22(1): 9-18. DOI:10.1177/1010539509355470 |

| [2] | Goel SA, Modi HN, Dave BR, et al. Socio economic impact of cervical spinal cord injuries operated in patients with lower income groups[J]. Global Spine J, 2016, 6(1 suppl). DOI:10.1055/s-0036-1582921 |

| [3] | Majdan M, Plancikova D, Nemcovska E, et al. Mortality due to traumatic spinal cord injuries in Europe: a cross-sectional and pooled analysis of population-wide data from 22 countries[J]. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med, 2017, 25: 64-74. DOI:10.1186/s13049-017-0410-0 |

| [4] | Montoto-Marqués A, Ferreiro-Velasco ME, Salvador-de LBS, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in Galicia, Spain: trends over a 20-year period[J]. Spinal Cord, 2017, 55(6): 588-594. DOI:10.1038/sc.2017.13 |

| [5] | Bjørnshave Noe B, Mikkelsen EM, Hansen RM, et al. Incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury in Denmark, 1990-2012: a hospital-based study[J]. Spinal Cord, 2015, 53(6): 436-440. DOI:10.1038/sc.2014.181 |

| [6] | Hasler RM, Exadaktylos AK, Bouamra O, et al. Epidemiology and predictors of cervical spine injury in adult major trauma patients: a multicenter cohort study[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2012, 72(4): 975-981. DOI:10.1097/TA.0b013e31823f5e8e |

| [7] | Tafida MA, Wagatsuma Y, Ma EB, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of traumatic spinal injury in Japan[J]. J Orthop Sci, 2018, 23(2): 273-276. DOI:10.1016/j.jos.2017.10.013 |

| [8] | Chen R, Liu X, Han S, et al. Current epidemiological profile and features of traumatic spinal cord injury in Heilongjiang province, Northeast China: implications for monitoring and control[J]. Spinal Cord, 2017, 55(4): 399-404. DOI:10.1038/sc.2016.92 |

| [9] | Chang FS, Zhang Q, Sun M, et al. Epidemiological study of spinal cord injury individuals from halfway houses in Shanghai, China[J]. J Spinal Cord Med, 2017, 41(4): 450-458. DOI:10.1080/10790268.2017.1367357 |

| [10] | Li HL, Xu H, Li YL, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in Tianjin, China: An-18-year retrospective study of 735 cases[J]. J Spinal Cord Med, 2018: 1-13. DOI:10.1080/10790268.8.2017.1415418 |

| [11] | Lee BB, Cripps RA, Fitzharris M, et al. The global map for traumatic spinal cord injury epidemiology: update 2011, global incidence rate[J]. Spinal Cord, 2014, 52(2): 110-116. DOI:10.1038/sc.2012.158 |

| [12] | Feng HY, Ning GZ, Feng SQ, et al. Epidemiological profile of 239 traumatic spinal cord injury cases over a period of 12 years in Tianjin, China[J]. J Spinal Cord Med, 2011, 34(4): 388-394. DOI:10.1179/2045772311Y.0000000017 |

| [13] | Yang R, Guo L, Wang P, et al. Epidemiology of spinal cord injuries and risk factors for complete injuries in guangdong, China: a retrospective study[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(1): e84733. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0084733 |

| [14] | Chamberlain JD, Deriaz O, Hundgeorgiadis M, et al. Epidemiology and contemporary risk profile of traumatic spinal cord injury in Switzerland[J]. Inj Epidemiol, 2015, 2(1): 28-39. DOI:10.1186/s40621015-0061-4 |

| [15] | Jain NB, Ayers GD, Peterson EN, et al. Traumatic spinal cord injury in the United States, 1993-2012[J]. JAMA, 2015, 313(22): 2236-2243. DOI:10.1001/jama.2015.6250 |

| [16] | Kriz J, Kulakovska M, Davidova H, et al. Incidence of acute spinal cord injury in the Czech republic:a prospective epidemiological study 2006-2015[J]. Spinal Cord, 2017, 55(9): 870-874. DOI:10.1038/sc.2017.20 |

| [17] | Umana E, Khan K, Baig MN, et al. Epidemiology and characteristics of cervical spine injury in patients presenting to a regional emergency department[J]. Cureus, 2018, 10(2): e2179. DOI:10.7759/cureus.2179 |

| [18] | Ramamurthy P, Kumar N, Osman A. Epidemiology, neurological and functional outcome of concomitant traumatic brain and spinal cord injury: An Oswestry experience[J]. Trauma, 2017, 19(1 suppl): 30-32. DOI:10.1177/1460408617718868 |

| [19] | Stothers L, Macnab AJ, Mukisa R, et al. Traumatic spinal cord injury in Uganda: a prevention strategy and mechanism to improve home care[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2017, 46(4): 1086-1090. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyx058 |

| [20] | Hua R, Shi J, Wang X, et al. Analysis of the causes and types of traumatic spinal cord injury based on 561 cases in China from 2001 to 2010[J]. Spinal Cord, 2013, 51(3): 218-221. DOI:10.1038/sc.201-2.133 |

| [21] | McCoy CE, Loza-Gomez A, Lee Puckett J, et al. Quantifying the risk of spinal injury in motor vehicle collisions according to ambulatory status: a prospective analytical study[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2017, 52(2): 151-159. DOI:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.09.024 |

| [22] | 陈坤, 戴建强, 张雷, 等. ICU内创伤性颈脊髓损伤的流行病学特点分析[J]. 中华急诊医学志, 2017, 26(10): 1167-1171. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2017.10.015 |

| [23] | 仲伟喜, 朱晓光, 杨开超, 等. 严重创伤患者中急性创伤性凝血病与深静脉血栓形成关系探讨[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2016, 25(5): 592-597. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2016.05.011 |

2019, Vol. 28

2019, Vol. 28