急性肾损伤(AKI)在危重病患者中经常发生[1-2],是危重症患者常见的合并症之一,尽管重症医学发展已经取得了巨大进步,但是AKI的预后仍然很差,发病率仍然很高[3], 其在ICU的病死率高达30%~60%[4]。持续肾脏替代治疗(CRRT)在维持患者血流动力学稳定,纠正内环境紊乱,清除代谢废物及炎症因子方面发挥着重要作用[5]。由于CRRT的主要优点是对血流动力学影响小,有近4%的AKI危重病患者需要接受肾脏替代治疗[6-7]。尽管维持合适的液体平衡是AKI患者治疗的基础,但对于最佳的液体治疗策略目前仍没有统一的意见。AKI传统的治疗策略是通过大量补液维持肾脏的灌注并且预防缺血性肾损伤进一步加剧,然而近期的研究表明容量过负荷(fluid overload, FO)与AKI危重病患者病死率增加密切相关[8-12],因此为了避免容量过负荷,对于这类患者的液体管理应更加严格精确。本研究旨在评价容量过负荷与接受CRRT的AKI危重病患者病死率之间的关系,可以为合理优化患者的液体管理策略提供参考依据,进而可能有助于改善AKI患者的预后。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料回顾性分析2012年1月至2017年6月入住吉林大学第一医院重症医学科(ICU)接受CRRT的成人AKI患者(年龄18~90岁)。CRRT的主要指征包括:非梗阻性少尿(尿量 < 400 mL/24 h)或无尿(尿量 < 100 mL/24 h),重度代谢性酸中毒(pH < 7.1),氮质血症(BUN > 30 mmol/L),药物应用过量且可被CRRT清除,高钾血症(K+ > 6.5 mmol/L)或血钾迅速升高,怀疑与尿毒症有关的心内膜炎、脑病、神经系统病变或肌病,严重的钠离子紊乱(血钠 > 160 μmol/L)以及容量过负荷。既往存在终末期肾病的患者被排除。最终入选本研究的患者共计261例,根据入ICU后30 d患者生存情况分为存活组(n=149)和死亡组(n=112)。

1.2 数据收集所有患者均应用金宝PRISMA血滤机及AN-69聚丙烯腈透析膜,CRRT模式包括持续静-静脉血液透析(CVVHD)、持续静-静脉血液滤过(CVVHF)及持续静-静脉血液透析滤过(CVVHDF)。CRRT的抗凝方法为枸橼酸钠抗凝,根据患者的血压、容量情况、血乳酸以及肾功能指标调整患者超滤量,CRRT的治疗剂量为25~30 mL/(kg·h)。统计入组患者的基线资料、合并症、临床数据、疾病严重程度(SOFA评分、血管活性药物数量、脓毒症、呼吸机使用)、容量过负荷情况以及从诊断AKI到CRRT开始的时间。比较存活组与死亡组患者基线资料的差异并进一步分析容量过负荷是否为入ICU后30 d病死率的危险因素。

1.3 相关定义AKI:根据KDIGO指南,血肌酐48 h内升高≥0.3 mg/dl,或血肌酐≥1.5倍基线水平,或尿量 < 0.5 mL/(kg·h)。CRRT:采用每天连续24 h或接近24 h的一种长时间、连续的体外血液净化疗法以替代受损的肾功能[13]。记录从CRRT开始前3 d到患者转出ICU时所有出入量数据,所有患者均留置导尿管用于尿量监测,对于不能得到CRRT开始前3 d的容量过负荷程度的病例予以排除。容量过负荷的程度以百分比(%FO)表示,计算公式如下:%FO=Σ[每日入量(L)-每日出量(L)]/基线体质量(kg)×100%。基线体质量以入院时测量的数据为准,容量过负荷定义为%FO≥10%[14]。根据患者容量过负荷的情况将患者分为容量过负荷组(n=92)及非容量过负荷组(n=169),比较两组患者的入ICU后30 d病死率的差异。

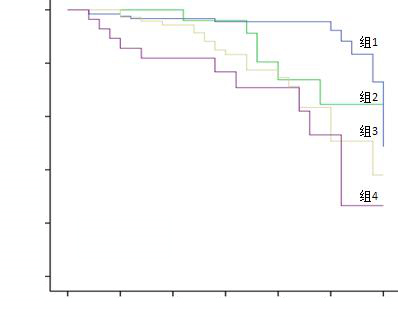

1.4 亚组分析%FO又被分为CRRT前%FO及CRRT后%FO,CRRT前%FO为CRRT开始前3 d的%FO,CRRT后%FO为从CRRT开始到患者转出ICU的%FO,总%FO=CRRT前%FO+CRRT后%FO。亚组分析分为4组,组1(n=130):CRRT前%FO < 10%且总%FO < 10%, 即CRRT前无容量过负荷,最终总液体无容量过负荷;组2(n=31):CRRT前%FO≥10%且总%FO < 10%,即CRRT前存在容量过负荷,但被CRRT清除,最终总液体无容量过负荷;组3(n=72):CRRT前%FO < 10%且总%FO≥10%,即CRRT前无容量过负荷,但由于CRRT期间大量补液导致总液体存在容量过负荷;组4(n=28):CRRT前%FO≥10%且总%FO≥10%,即CRRT前存在容量过负荷并没有被CRRT解除,最终总液体仍存在容量过负荷。比较4组患者入ICU后30 d病死率的差异。

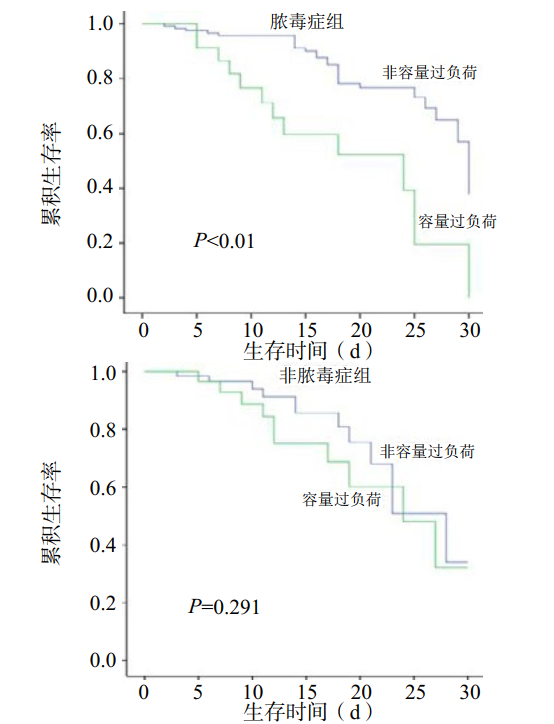

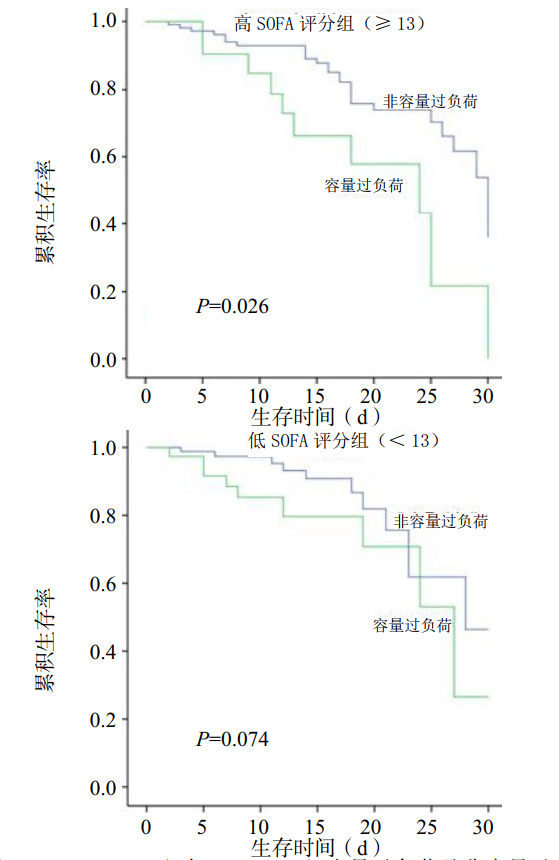

根据SOFA评分将患者分为高SOFA(≥13)组(n=135)和低SOFA(< 13)组(n=126)。分别比较两组患者中容量过负荷与非容量过负荷患者入ICU后30 d病死率的差异。根据脓毒症发生情况将患者分为脓毒症组(n=154)和非脓毒症组(n=107),分别比较两组患者中容量过负荷与非容量过负荷患者入ICU后30 d病死率的差异。

1.5 统计学方法应用SPSS 19.0统计软件进行分析,计量资料用均数±标准差(Mean±SD)表示,比较采用成组t检验或Mann-Whitney U检验;计数资料比较采用χ2检验或Fisher确切概率法检验。入ICU后30 d病死率相关影响因素的分析采用多元logistic回归分析,采用Kaplan-Meier生存曲线分析比较各亚组入ICU后30 d病死率的差异,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 比较存活组和死亡组患者的基线资料两组患者的性别、年龄、基线体质量、慢性肾脏疾病、高血压、糖尿病、入ICU时体温、心率、血清尿素氮、血钾、白细胞、血红蛋白、C反应蛋白、pH、脓毒症、每日绝对容量平衡、容量过负荷持续时间等指标比较差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05),见表 1。

| 指标 | 存活组 (n=149) |

死亡组 (n=112) |

t值/ F值 | P值 |

| 人口统计学资料 | ||||

| 年龄(岁)a | 58.4±15.8 | 60.7±15.2 | 1.21 | 0.18 |

| 男性(例,%) | 107(71.8) | 76(67.9) | 3.54 | 0.43 |

| 基线体质量(kg)a | 62.4±9.4 | 61.9±11.4 | -0.27 | 0.15 |

| 合并症(例,%) | ||||

| 慢性肾脏疾病 | 30(20.1) | 26(23.2) | 5.45 | 0.32 |

| 高血压 | 65(43.6) | 51(45.5) | 3.65 | 0.68 |

| 糖尿病 | 34(22.8) | 35(31.3) | 7.76 | 0.12 |

| 慢性阻塞性肺疾病 | 7(4.7) | 14(12.5) | 1.24 | 0.006 |

| 肝硬化 | 14(9.4) | 25(22.3) | 3.56 | 0.001 |

| 充血性心力衰竭 | 12(8.1) | 24(21.4) | 2.54 | < 0.01 |

| 入ICU时指标 | ||||

| 平均动脉压(mmHg)a | 80.6±18.0 | 71.1±14.2 | 0.56 | < 0.01 |

| 发热或低体温(例,%) | 28(18.8) | 28(25.0) | -0.76 | 0.12 |

| 心率(次/min)a | 100.8±42.5 | 104.6±53.0 | 1.76 | 0.62 |

| 少尿[ < 0.5 mL/(kg·h)](例,%) | 48(32.2) | 55(49.1) | 0.78 | 0.002 |

| 血肌酐(mg/dl)a | 4.3±1.6 | 4.9±2.4 | 2.46 | 0.02 |

| 血清尿素氮(ng/dl)a | 82.2±39.7 | 85.1±49.2 | -0.27 | 0.42 |

| 血钾(mmol/L)a | 4.8±1.0 | 4.9±1.0 | 1.35 | 0.29 |

| 白细胞(×109/L)a | 14.3±15.8 | 17.6±24.9 | 0.52 | 0.18 |

| 血红蛋白(g/L)a | 105.2±22.1 | 103.2±24.2 | 0.76 | 0.47 |

| 血小板(×109/L)a | 152.2±99.1 | 117.8±85.1 | 1.36 | < 0.01 |

| C反应蛋白(mg/dl)a | 13.7±13.5 | 14.4±11.7 | 2.24 | 0.58 |

| pHa | 7.3±1.3 | 7.3±0.1 | 1.54 | 0.33 |

| 疾病严重程度 | ||||

| 脓毒症(例,%) | 87(58.4) | 66(58.9) | -0.21 | 0.88 |

| SOFA评分a | 10.0±4.2 | 14.4±4.1 | 3.43 | < 0.01 |

| 使用升压药数量a | 0.9±1.0 | 1.5±1.0 | 1.34 | 0.001 |

| 呼吸机依赖(例,%) | 78(52.3) | 89(79.5) | 2.12 | < 0.01 |

| 每日绝对容量平衡(mL)a | 765±235 | 856±265 | 1.56 | 0.08 |

| 容量过负荷情况 | ||||

| 总%FO≥10%(例,%) | 38(25.5) | 51(45.5) | 1.37 | 0.001 |

| FO持续时间(d)a | 4.5±2.3 | 4.8±2.8 | 3.56 | 0.89 |

| 从诊断AKI到CRRT开始的天数a | 2.2±3.0 | 3.8±2.8 | 4.32 | < 0.01 |

| 注:SOFA评分,序贯器官衰竭估计评分; %FO,容量过负荷百分比;a为Mean±SD | ||||

两组患者的慢性阻塞性肺疾病(P=0.006)、肝硬化(P=0.001)、充血性心力衰竭(P < 0.01)、入ICU时平均动脉压(P < 0.01)、少尿(P=0.002)、血肌酐(P=0.02)、血小板(P < 0.01)、SOFA评分(P < 0.01)、使用升压药数量(P=0.001)、呼吸机依赖(P < 0.01)、容量过负荷(P=0.001)、从诊断AKI到CRRT开始的天数(P < 0.01)等指标比较差异均有统计学意义,见表 1。

2.2 入ICU后30 d病死率的相关危险因素分析比较存活组和死亡组患者的临床资料,对单因素分析有统计学意义的变量进行多元logistic回归分析。如表 2所示,总%FO≥10%(OR=1.30,95%CI:1.13~2.05,P=0.01)、呼吸机依赖(OR=1.65,95%CI:1.01~2.55,P=0.03)、少尿(OR=1.55,95%CI:1.13~2.15,P=0.01)、SOFA评分≥13(OR=1.15,95%CI:1.01~1.20,P < 0.01)、从诊断AKI到CRRT开始 > 3天(OR=1.03,95%CI:1.01~1.13,P=0.04)以及平均动脉压 < 72 mmHg(OR=1.10,95%CI:1.00~1.30,P=0.04)时,接受CRRT的急性肾损伤患者30 d死亡风险显著增高,提示容量过负荷、呼吸机依赖、少尿、SOFA评分≥13、从诊断AKI到CRRT开始 > 3 d、平均动脉压 < 72 mmHg是接受CRRT的急性肾损伤患者30 d病死率的独立危险因素。而充血性心力衰竭、慢性阻塞性肺疾病、血肌酐≥4.9 mg/dl、血小板计数 < 118×109/L、肝硬化及使用升压药数量≥2种对接受CRRT的急性肾损伤患者30 d病死率无明显影响。

| 因素 | β值 | OR值 | 95%CI | P值 |

| 总%FO≥10% | 1.01 | 1.30 | 1.13~2.05 | 0.01 |

| 呼吸机依赖 | 0.67 | 1.65 | 1.01~2.55 | 0.03 |

| 少尿 | 0.23 | 1.55 | 1.13~2.15 | 0.01 |

| SOFA评分≥13 | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.01~1.20 | < 0.01 |

| 从诊断AKI到CRRT开始 > 3 d | 0.67 | 1.03 | 1.01~1.13 | 0.04 |

| 平均动脉压 < 72 mmHg | 0.54 | 1.10 | 1.00~1.30 | 0.04 |

| 充血性心力衰竭 | 1.54 | 1.09 | 0.74~1.65 | 0.66 |

| 慢性阻塞性肺疾病 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 0.76~1.33 | 0.98 |

| 血肌酐≥4.9 mg/dl | 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.97~1.16 | 0.60 |

| 血小板计数 < 118×109/L | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99~1.00 | 0.52 |

| 肝硬化 | 1.46 | 1.08 | 0.73~1.66 | 0.64 |

| 升压药数量≥2 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 0.78~1.13 | 0.46 |

| 注:%FO,容量过负荷百分比;SOFA评分,序贯器官衰竭估计评分 | ||||

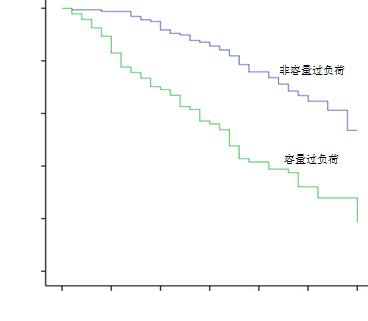

容量过负荷组(n=92)较非容量过负荷组患者(n=169)的30 d生存率明显降低(P < 0.01),见图 1。

|

| 图 1 容量过负荷组与非容量过负荷组患者的Kaplan-Meier生存曲线 Figure 1 Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients in the fluid overload group and the non-fluid overload group |

|

|

比较四个亚组患者的生存率,差异有统计学意义,组1 > 组2 > 组3 > 组4(P < 0.01),见图 2。

|

| 组1(n=130):CRRT前%FO < 10%且总%FO < 10%;组2(n=39):CRRT前%FO≥10%且总%FO < 10%;组3(n=64):CRRT前%FO < 10%且总%FO≥10%;组4(n=28):CRRT前%FO≥10%且总%FO≥10% 图 2 四组患者Kaplan-Meier生存曲线 Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the four groups |

|

|

根据患者是否存在脓毒症将患者分为脓毒症组(n=154)和非脓毒症组(n=107)。脓毒症组容量过负荷(n=62)与非容量过负荷(n=92)患者30 d生存率差异有统计学意义(P < 0.01),非脓毒症组容量过负荷(n=31)与非容量过负荷(n=76)患者的30 d生存率差异无统计学意义(P=0.291),见图 3。

|

| 图 3 脓毒症组与非脓毒症组容量过负荷及非容量过负荷患者Kaplan-Meier生存曲线 Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier survival curves in the septic and non-septic groups with fluid overload and non -fluid overload |

|

|

根据患者SOFA评分将患者分为SOFA≥13组(n=135)与SOFA < 13组(n=126)。SOFA≥13组容量过负荷(n=57)与非容量过负荷(n=78)患者的30 d生存率差异有统计学意义(P=0.026),SOFA < 13组容量过负荷(n=35)与非容量过负荷(n=91)患者的30 d生存率差异无统计学意义(P=0.074),见图 4。

|

| 图 4 SOFA≥13组与SOFA < 13组容量过负荷及非容量过负荷患者Kaplan-Meier生存曲线 Figure 4 Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with SOFA≥13 and SOFA < 13 with fluid overload and non -fluid overload |

|

|

液体复苏对于维持重症患者血流动力学稳定具有重要意义。对于严重脓毒症和脓毒性休克患者早期及时的液体复苏至关重要[15]。然而,如果液体复苏超过一定阈值,容量过负荷其实是有害的。实际上已有研究报道容量过负荷可增加急性肺损伤和脓毒性休克患者的病死率[16-19]。近期有两项大规模研究已表明,AKI患者容量过负荷与病死率增加密切相关。SOAP研究入组的3 147例患者中有1 120例发生AKI且60 d病死率(36%)高于非AKI组(15%)。在AKI组中液体正平衡(1 L/24 h)会使60 d死亡风险增加近20%[17]。在PICARD研究中,容量过负荷与病死率增加的相关性更加明显,在入组的618例AKI患者中,容量过负荷组较非容量过负荷组患者住院病死率(48% vs 35%)、30 d病死率(37% vs 25%)及60 d病死率(46% vs 32%)均明显增加[12]。

本研究表明容量过负荷会降低患者的生存率,这与之前的报道是一致的。从CRRT开始前3天到患者转出ICU存在容量过负荷的AKI患者与非容量过负荷患者相比生存率明显降低,容量过负荷患者病死率是非容量过负荷患者的1.53倍。此外亚组分析中,第4组患者病死率最高,其次是第3组、第2组,第1组病死率最低,这个结果表明通过CRRT清除多余的液体可以降低患者的病死率。

这项研究中病死率的一个重要的预测因素是从诊断AKI到CRRT开始的时间,CRRT的启动时机仍然是存在争议的,一些研究推荐合并AKI的重症患者早期启动CRRT[20-22],但也有一些回顾性研究发现早期和晚期CRRT对生存率无影响[23]。本研究表明从诊断AKI到CRRT开始的延迟时间与病死率增加密切相关,尽管本研究为回顾性研究,结果提示合并AKI的重症患者早期启动CRRT可以改善患者预后。

本研究的主要发现是容量过负荷对于生存率的不良影响在脓毒症或重症患者(SOFA≥13)中更加明显,在脓毒症或高SOFA评分的患者中,容量过负荷患者的生存率低。通常来说脓毒症AKI被认为是AKI的缺血型,通过液体复苏增加肾脏灌注被认为是治疗的基础。然而近期的研究表明脓毒症AKI与非脓毒症AKI病理生理学机制不同,脓毒症AKI发病机制复杂且缺乏病理资料,可能存在以下几点:①血流动力学与应激激素的变化。脓毒症时肾脏微血管系统与全身其他部位血管床不同,表现为对血管收缩物质的正常反应甚至反应增加,造成肾血流量和肾小球滤过率的下降。②内毒素和炎症介质的影响。在内毒素的作用下,中性粒细胞、单核细胞、血管内皮细胞发生复杂的免疫反应,释放大量内源性炎症介质,直接造成肾脏受损。③细胞凋亡。研究表明细胞凋亡是脂多糖诱导的急性肾损伤的机制之一。④弥漫性血管内凝血(diffuse intravascular coagula, DIC)。脓毒症诱发凝血和纤溶系统反应,使肾小球内形成微血栓,堵塞肾脏微血管。其中炎症反应在脓毒症AKI发生发展中居核心地位[24],因此超过复苏终点的大量补液治疗脓毒性症AKI的合理性受到质疑[25-28],而通过CRRT清除炎症介质可以减轻肾脏损害并且保护肾功能[29]。

综上所述,本研究结果表明容量过负荷与合并AKI重症患者的病死率增加密切相关。通过CRRT清除多余的液体可以降低AKI重症患者的病死率。对于脓毒症或重症(SOFA≥13)患者,容量过负荷对生存率的不良影响更加明显。因此对于这类患者需要执行更加严格的液体管理策略,从而避免容量过负荷的发生。

| [1] | Bagshaw SM, George C, Dinu I, et al. A multi-centre evaluation of the RIFLE criteria for early acute kidney injury in critically ill patients[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2008, 23(4): 1203-1210. DOI:10.1093/ndt/gfm744 |

| [2] | Hoste EA, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2006, 10(3): R73. DOI:10.1186/cc4915 |

| [3] | Waikar SS, Curhan GC, Wald R, et al. Declining mortality in patients with acute renal failure, 1988 to 2002[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2006, 17(4): 1143-1150. DOI:10.1681/asn.2005091017 |

| [4] | Palevsky PM. Renal support in acute kidney injury--how much is enough?[J]. N Engl J Med, 2009, 361(17): 1699-1701. DOI:10.1056/NEJMe0907831 |

| [5] | Ronco C, Levin A, Warnock DG, et al. Improving outcomes from acute kidney injury (AKI): Report on an initiative[J]. Int J Artif Organs, 2007, 30(5): 373-376. DOI:10.1177/039139880703000503 |

| [6] | Ricci Z, Ronco C, D'Amico G, et al. Practice patterns in the management of acute renal failure in the critically ill patient: an international survey[J]. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2006, 21(3): 690-696. DOI:10.1093/ndt/gfi296 |

| [7] | Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study[J]. JAMA, 2005, 294(7): 813-818. DOI:10.1001/jama.294.7.813 |

| [8] | Goldstein SL, Currier H, Graf Cd, et al. Outcome in children receiving continuous venovenous hemofiltration[J]. Pediatrics, 2001, 107(6): 1309-1312. DOI:10.1542/peds.107.6.1309 |

| [9] | Foland JA, Fortenberry JD, Warshaw BL, et al. Fluid overload before continuous hemofiltration and survival in critically ill children: a retrospective analysis[J]. Crit Care Med, 2004, 32(8): 1771-1776. DOI:10.1097/01.ccm.0000132897.52737.49 |

| [10] | Gillespie RS, Seidel K, Symons JM. Effect of fluid overload and dose of replacement fluid on survival in hemofiltration[J]. Pediatr Nephrol, 2004, 19(12): 1394-1399. DOI:10.1007/s00467-004-1655-1 |

| [11] | Payen D, de Pont AC, Sakr Y, et al. A positive fluid balance is associated with a worse outcome in patients with acute renal failure[J]. Crit Care, 2008, 12(3): R74. DOI:10.1186/cc6916 |

| [12] | Bouchard J, Soroko SB, Chertow GM, et al. Fluid accumulation, survival and recovery of kidney function in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury[J]. Kidney Int, 2009, 76(4): 422-427. DOI:10.1038/ki.2009.159 |

| [13] | 血液净化急诊临床应用专家共识组. 血液净化急诊临床应用专家共识[J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2017, 26(1): 24-36. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1671-0282.2017.01.007 |

| [14] | Kim IY, Kim JH, Lee DW, et al. Fluid overload and survival in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury receiving continuous renal replacement therapy[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(2): e0172137. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0172137 |

| [15] | Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock[J]. N Engl J Med, 2001, 345(19): 1368-1377. DOI:10.1056/nejmoa010307 |

| [16] | Alsous F, Khamiees M, DeGirolamo A, et al. Negative fluid balance predicts survival in patients with septic shock: a retrospective pilot study[J]. Chest, 2000, 117(6): 1749-1754. DOI:10.1378/chest.117.6.1749 |

| [17] | Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34(2): 344-353. DOI:10.1097/01.ccm.0000194725.48928.3a |

| [18] | Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury[J]. N Engl J Med, 2006, 354(24): 2564-2575. DOI:10.1056/nejmoa062200 |

| [19] | Boyd JH, Forbes J, Nakada TA, et al. Fluid resuscitation in septic shock: a positive balance and elevated central venous pressure are associated with increased mortality[J]. Crit Care Med, 2011, 39(2): 259-265. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feeb15 |

| [20] | Piccinni P, Dan M, Barbacini S, et al. Early isovolaemic haemofiltration in oliguric patients with septic shock[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2006, 32(1): 80-86. DOI:10.1007/s00134-005-2815-x |

| [21] | Liu KD, Himmelfarb J, Paganini E, et al. Timing of initiation of dialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury[J]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2006, 1(5): 915-919. DOI:10.2215/CJN.01430406 |

| [22] | Kielstein JT, Kretschmer U, Ernst T, et al. Efficacy and cardiovascular tolerability of extended dialysis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled study[J]. Am J Kidney Dis, 2004, 43(2): 342-349. DOI:10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.021 |

| [23] | Bouman CS, Oudemans-Van Straaten HM, Tijssen JG, et al. Effects of early high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration on survival and recovery of renal function in intensive care patients with acute renal failure: a prospective, randomized trial[J]. Crit Care Med, 2002, 30(10): 2205-2211. DOI:10.1097/00003246-200210000-00005 |

| [24] | Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, et al. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study[J]. JAMA, 1995, 273(2): 117-123. DOI:10.1001/jama.1995.03520260039030 |

| [25] | Jacobs R, Honore PM, Joannes-Boyau O, et al. Septic acute kidney injury: the culprit is inflammatory apoptosis rather than ischemic necrosis[J]. Blood Purif, 2011, 32(4): 262-265. DOI:10.1159/000330244 |

| [26] | Wan L, Bagshaw SM, Langenberg C, et al. Pathophysiology of septic acute kidney injury: what do we really know?[J]. Crit Care Med, 2008, 36(4 Suppl): S198-203. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168ccd5 |

| [27] | Licari E, Calzavacca P, Ronco C, et al. Fluid resuscitation and the septic kidney: The evidence[M]//Licari E, Calzavacca P, Ronco C, et al. eds. Contributions to nephrology. Basel: KARGER, 2007: 167-177. DOI: 10.1159/000102080. |

| [28] | Langenberg C, Wan L, Egi M, et al. Renal blood flow and function during recovery from experimental septic acute kidney injury[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2007, 33(9): 1614-1618. DOI:10.1007/s00134-007-0734-8 |

| [29] | Xu JJ, Zhen JT, Tang L, et al. Intravenous injection of Xuebijing attenuates acute kidney injury in rats with paraquat intoxication[J]. World J Emerg Med, 2017, 8(1): 61-64. DOI:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2017.01.011 |

2019, Vol. 28

2019, Vol. 28